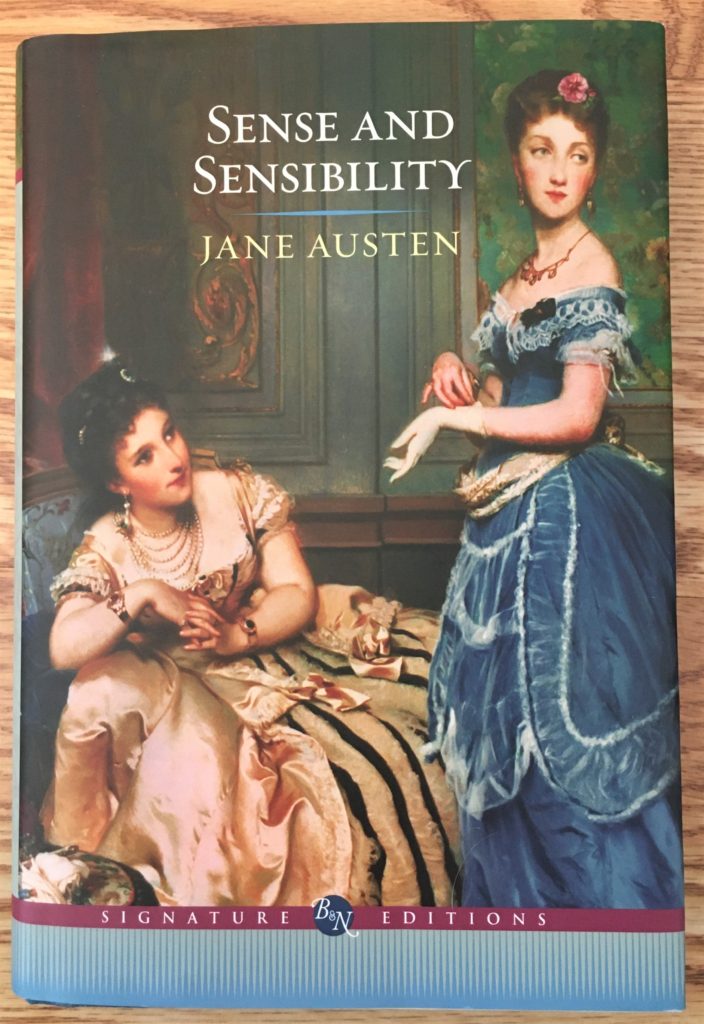

by Jane Austen

copyright: 1811

from Barnes & Noble signature editions

I have read Jane Austen’s novel several times over the years, and I have to say that it never gets old. This time especially, re-reading “Sense and Sensibility” was like falling into a rich, warm, language/plot/character bath. I had just read several books that I felt obligated to read; most of which I had found boring, not well written, offensive and/or depressing. “Sense and Sensibility” was perfect for soothing my soul and giving my brain a re-charge.

Even though “Sense and Sensibility” has been reviewed many times by Austen scholars, high school and college students, and many others, I wanted to write a review of this book for several reasons. First, just because I like it and it is a really good story! Second because of what I had already stated, this book recharged my reading energy after a few not-so-great reads. And third, because for whatever reason, Austen’s humor struck such a fun note in my reading this time around. She had such a gift of language.

Much of the humor (and I would add growth of the characters) comes from the contrast of “sense” or logical, methodical thinking, and “sensibility” or letting one’s emotions rule their actions and their decision making. The two main characters, the sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood are the respective examples of these two ideas.

These few words from Chapter One, describes the older sister, Elinor and much of the source of conflict to come:

“She had an excellent heart; her disposition was affectionate, and her feelings were strong; but she knew how to govern them: it was knowledge which her mother had yet to learn, and which one of her sisters resolved never to be taught.”

By Chapter Eleven, Willoughby has become a very important young man in Marianne’s life and because the two have such similar views of life, they do tend to be a bit over the top much to Elinor’s dismay.

“Elinor could not be surprised at their attachment. She only wished that it were less openly shown; and once or twice did venture to suggest the propriety of some self-command to Marianne. But Marianne abhorred all concealment where no real disgrace could attend unreserve; and to aim at the restraint of sentiments which were not in themselves illaudable, appeared to her not merely an unnecessary effort, but a disgraceful subjection of reason to common-place and mistaken notions. Willoughby thought the same; and their behavior, at all times, was an illustration of their opinions.”

I love this: “and their behavior, at all times, was an illustration of their opinions.” I grin inside when I read it, but it also makes me understand with perfect clarity the problem of unrestrained “sensibility”. In some ways sensibility is commendable; what you believe and how you act are in alliance. I think Elinor would say that you can have your actions in line with your beliefs without being extravagant in your display of what you believe in every instance. As when Marianne, grief stricken over Willoughby’s eventual betrayal, literally makes herself sick.

In Chapter Sixteen one of my favorite little scenes occurs as Elinor’s especial friend, Edward, arrives for a visit by way of the family’s former home “Norland”.

“And how does dear, dear Norland look?” cried Marianne.

“Dear, dear Norland,” said Elinor, “probably looks much as it always does at this time of year. The woods and walks thickly covered with dead leaves.”

“Oh!” cried Marianne, “with what transporting sensations have I formerly seen them in fall! How have I delighted, as I walked, to see them driven in showers about me by the wind! What feelings have they, the season, the air altogether inspired! Now there is no one to regard them. They are only seen as a nuisance, swept hastily off, and driven as much as possible from sight.”

“It is not everyone,” said Elinor, “who has your passion for dead leaves.”

I chuckled again as I typed out the quote. Perhaps I like it because it illustrates the difference between sense and sensibility not only so well, but so harmlessly and with such dry humor. I will admit I tend to fall on the side of Marianne in this instance. I think my family can attest that I can be overly rapturous of the natural world around me.

Other characters in the story also lend us a bit of humor, for example:

“I was therefore entered at Oxford and have been properly idle ever since.”

“But, poor fellow! It is very fatiguing to him! For he is forced to make everybody like him.”

“Lady Middleton resigned herself to the idea of it, with all the philosophy of a well-bred woman, contenting herself with merely giving her husband a gentle reprimand on the subject five or six times every day.”

These little nuggets are pure gold as I read along when Austen inserts something unexpected, and being unexpected, wakes me up and makes me laugh out loud!

While the tension of the story is often relayed by the differences of “sense” and “sensibility” as basic outlooks of life, Jane Austen herself doesn’t really seem to favor one point of view over the other. I think one way that she makes that clear is Elinor and Marianne’s true devotion and love for each other as sisters. While Elinor hopes for Marianne to gain some control over her emotions, she does not berate her for who she is. And on Marianne’s part, she does not understand Elinor’s reserve, but she loves her just the same and becomes even more loyal to her when she learns of Elinor’s private distress.

It seems Elinor’s sense may be better but, she also suffers dreadfully because she does not express herself or let anyone comfort her who would have if they had only known of her suffering. While Marianne’s sensibility seems to undermine her happiness, she also can find joy in the smallest of things and her music is a great comfort to her. Both sisters change to the degree of letting in a bit of the other’s philosophy to make a happier whole. Throughout this journey to ultimate happiness for the sisters, Austen employs wonderful conversation using beautiful language, peppered with bits of humor to make this book a truly enjoyable read.

“It is not everyone,” said Elinor, “who has your passion for dead leaves.”

This section is my absolute Favorite!!!

😊

Wow…this review could move me to read some Austen!!! 😁 I haven’t picked up a Jane Austen book since Pride and Prejudice back in college. (I remember my roommate had that Lit class the semester before me and she seemed to be reading that book for the WHOLE SEMESTER…I remember thinking: Gosh, that must be a really hard book…it’s taking her forever to get through it! 🤣) When it came my turn, I think it took me awhile to read too! Maybe I wasn’t mature enough to enjoy her writing? After reading your review, I think there must be a certain delicacy to J.A.’s writing that I wasn’t quite able to pick up on back then? Anyway, I will now put Sense and Sensibility on my list!

That is an interesting idea; I hadn’t thought of Jane Austen’s writing as delicate, but maybe from our modern view point it could be considered so. I do know her books tend to be scathing in their critique of her society in the time in which she lived. I certainly did not catch that when I first discovered her and devoured all her books when I was a college student. If you do read it, I hope you enjoy it as much as I have!!